Why is the IU School of Medicine Located in Indianapolis?

The IU School of Medicine has been a very influential part of Indiana University and the state of Indiana for over a century. Just on its own terms, it is quite a large enterprise. At its last accreditation in 2017, the school reported an annual income exceeding $1.5 billion. More than 2,000 full-time faculty taught 1,350 MD students, and there were roughly an equal number of residents. Its external research funding topped $250 million.

Parts of the history of the school are well known, but one of the most often asked questions remains: Why is the medical school located in Indianapolis and not Bloomington? The answer is that the medical school is based where most of the doctors and patients were—Indianapolis, not Bloomington.

The creation of the medical school was a complicated process.

The state-supported college in Bloomington was authorized for medical instruction in 1838 when its name was changed from Indiana College to Indiana University, but the school did not offer medical instruction until 1871. That is when IU made an agreement with Indiana Medical College, established the year before in Indianapolis, to make it the university’s Medical Department. Graduates of the five-month course still required years of apprenticeship, but the university failed to receive any state funding for medical instruction, so the partnership ended in 1876.

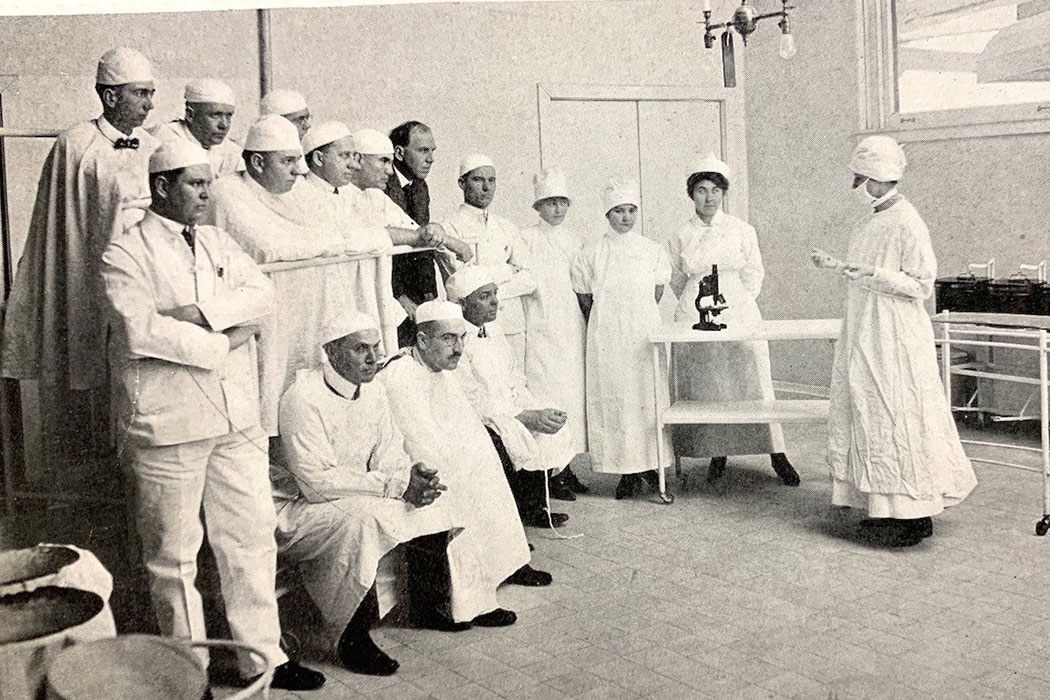

Private medical schools continued to attract students, and as medical knowledge grew, they extended the length of coursework and arranged for clinical instruction at the new hospitals, especially those established in Indianapolis. The increased cost of this instruction and the beginnings of accreditation led the private schools to seek college and university partners. For example, the largest medical school in Indianapolis, the Medical College of Indiana, attempted to collaborate with Indiana Asbury (later Depauw) and Butler, but these alliances were short-lived.

Soon after 1902, when William Lowe Bryan, BA 1884, MA 1886, LLD’37, became president of IU, he proposed reestablishing medical instruction and approached the Indianapolis schools. When these discussions produced little agreement, the president decided to begin offering what by then had become the first two years of instruction in medical science (anatomy and physiology) and laboratory subjects (e.g., bacteriology), both of which could be accommodated in the current science facilities in Bloomington with limited additional faculty. For clinical instruction, however, students had to transfer to schools in larger cities like Indianapolis, where hospitals had the patients and doctors who could instruct students in clinical care. In 1900, Bloomington had only 6,400 people—whereas Indianapolis was home to 170,000.

Complicating matters, however, was Purdue University President Winthrop E. Stone, who entered the scene and secured agreements with the two largest schools in Indianapolis (Medical College of Indiana and the Central College of Physicians and Surgeons), thus creating the Medical Department of Purdue University. This strategy was strongly resisted by IU, and, in 1908, after a few years of what was called “a battle” in the press and legislature, Bryan finally reached an agreement with Stone whereby the Indianapolis schools joined IU. Initially, the first two years of instruction continued at Bloomington while the four-year curriculum of the merged Indianapolis schools also continued. But this awkward duplication was resolved a few years later when the president secured an agreement to have the first year taught only at Bloomington and the rest of instruction to be given in Indianapolis. This arrangement continued for another 45 years.

During that time, the program was a surprising success and included the rapid construction of multiple hospitals on what became the campus adjacent to the Indianapolis City Hospital, west of downtown. This was largely the result of local philanthropy, matched by state support that made possible the construction of Long Hospital (opened in 1914), Riley Hospital (opened in 1924), and Coleman maternity hospital (opened in 1927).

The IU School of Medicine was able to survive and even continue to grow during the Great Depression and World War II. The biggest and most dramatic change in medical instruction came between the late 1950s through the early 1970s, when the school shifted from an attempt to consolidate instruction in Indianapolis to an effort to distribute it around the state. The resulting statewide system is now the single most identifiable feature of the IU medical school nationally.

This process began with the opening of the Medical Building in Indianapolis in 1958, a project that responded to increasing criticism of the division of instruction between Bloomington and Indianapolis that dated back to the 1930s. It also increased facilities for larger enrollments and enabled the recruitment of full-time faculty with a research agenda, a growing necessity in American medical education, thanks to the tremendous increase in available federal medical research funds following World War II. In 1958, the Medical Building (now Van Nuys Hall) opened and admitted first-year medical students in Indianapolis for the first time since 1911. The departments of anatomy and physiology were established, and the number of incoming students grew from 158 in 1957 to 215 in 1965. This gave the IU School of Medicine one of the largest MD classes in the U.S.

Despite this growth, which was especially welcomed by the state legislature, within 10 years the medical school reversed its efforts at consolidation and began establishing the decentralized statewide program that exists today.

What caused this change? It started when a report issued by the U.S. Surgeon General’s consultant group on medical education in October 1959 warned of a shortage of physicians. The report sparked a national discussion about the future supply of physicians in the United States, and a call by local politicians for more medical schools. (That report from the Surgeon General was later found to include errors regarding assumptions about population growth and the identification of regions predicted for shortages. By the end of the 1970s, for a number of reasons, the medical professions and schools were most concerned about a glut of MDs.)

The call for more schools soon included Indiana, despite the fact that the IU medical school was in the middle of expanding enrollment by 35 percent. In fact, the school’s main focus had shifted to problems with its residency program, a much better predictor of where physicians would eventually practice. The state’s only medical school was graduating over 150 students per year in the early 1960s, but the state had only just over 100 internship slots.

As a result, throughout 1963, IU School of Medicine Dean John Van Nuys sought support for expansion of graduate medical education, but outside of Indianapolis the subtle relationship between medical graduates, residencies, and medical practice was not well understood. Instead, local politicians and business heads around the state, and Gov. Matthew E. Welsh, LLD’61, in August 1963, called for a second medical school to be established. Leaders in cities such as Muncie, South Bend, and Gary were less interested in graduate medical education and much more eager to see the expansion of medical education and accompanying economic development in their regions through the establishment of a new medical school.

In response, the IU Board of Trustees quickly moved to defend its “statutory responsibility for medical education” in the state by commissioning in November 1963 a study to examine the development of medical education in Indiana. This proved to be the first of at least six committees that issued reports between 1964 and 1969. During this time, Glen Irwin, BS’42, MD’44, LLD’86—who became dean following Van Nuys’s untimely death in February 1964—took the lead in gaining support for a compromise statewide plan whereby half of the first two years of instruction was provided at eight sites around the state and the other half in Indianapolis. Then all students would finish their degrees in Indianapolis.

A couple of circumstances enabled such a dramatic change. First, was the rivalry over the decision about the location of a second school, with each of the other locations facing off against any one site that was gaining support in the legislature. A second compelling argument was the cheaper cost of expanding initial medical science instruction, as opposed to the much greater expense of creating a whole new medical school with all the necessary faculty and facilities, especially laboratories and clinical hospitals.

As a result, the medical school sought locations for medical science instruction, if possible where there were university facilities. The campus in Bloomington had already been doing this on a small scale as part of the agreement to consolidate instruction in Indianapolis. A dozen or so students were allowed to receive the first two years of medical science instruction (and a MS degree) before transferring to complete their medical degree in Indianapolis. Following this example, in 1968 when agreements were reached with Purdue and Notre Dame, the first few students began instruction in what became pilot programs in West Lafayette and South Bend.

Implementation, however, proved to be quite complex, requiring selection of facilities and qualified faculty and establishment of lines of responsibility with multiple institutions at all the locations. In addition, the medical school had to make the case, especially to accrediting agencies, that students received the same education in all of these varied settings. Nonetheless, by 1981, the first year of instruction was being offered to half of the entering students at all the sites around the state, and by 1990, the second year had been added. This plan continued until the early 2000s when, following predictions of another physician shortage, the IU School of Medicine moved to expand instruction of the last two years of the program at the sites around the state, a goal that was achieved by 2014.

In conclusion, the answer to why the IU School of Medicine is not in Bloomington is that there were not enough doctors and patients at that location to train physicians. If the greatest number of doctors has always been in Indianapolis, why isn’t the whole medical school there? The most important reason is politics, and the best proof is found in the nature of the second medical school in the state which finally opened in 2013. It was established without state funding (or political influence) at Marian University with the assistance of the American Osteopathic Association, and the location is not only in Indianapolis, but just two miles down the road from the IU School of Medicine.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine, a special six-issue magazine that highlights Bicentennial activities and shares untold stories from the dynamic history of Indiana University. Visit 200.iu.edu for more Bicentennial information.

Tags from the story

Written By

William Schneider

William is a professor of history on the IUPUI campus, and a contributor to 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine.