What is a Drunk-O-Meter? How IU Research Made Your Streets Safer

“It is also of my opinion that little money could actually be made out of it. However, maybe there is a greater demand for this type of equipment than many of us know. At least it is a start toward what may be a bigger and better undertaking.”

Those were the words of Indiana University Foundation’s legal counsel in 1936, while considering the commercial viability of a new invention by Dr. Rolla Harger, a biochemistry and toxicology professor at the IU School of Medicine. Little did he know, the device, utilized to measure the amount of alcohol in an individual’s breath, would herald a sea change in law-enforcement and traffic safety. The device was called the Drunk-O-Meter.

Rolla Harger, a native of Kansas, began his career as a chemistry student at Washburn College, where he reportedly bred and sold mules to help pay tuition. Harger joined the IU School of Medicine in 1922, shortly after receiving his doctorate from Yale. While a member of IU’s faculty, he devoted a significant portion of his time to determining the relationship between the level of alcohol in an individual’s blood to the amount present in their breath, research that culminated in his 1931 invention of the Drunk-O-Meter, patented in 1935.

Harger created the Drunk-O-Meter in response to the serious drunk-driving problem that had emerged in 1930s–40s America, stemming from both prohibition and an increasing dependency on automobiles for transportation. Harger’s research was among the first to determine the blood-alcohol limits beyond which a driver was seriously impaired, described as “dizzy and delirious” at BAC 0.15 (nearly twice today’s legal limit) and to provide a device which could quickly and conveniently measure someone’s blood-alcohol content using only their breath.

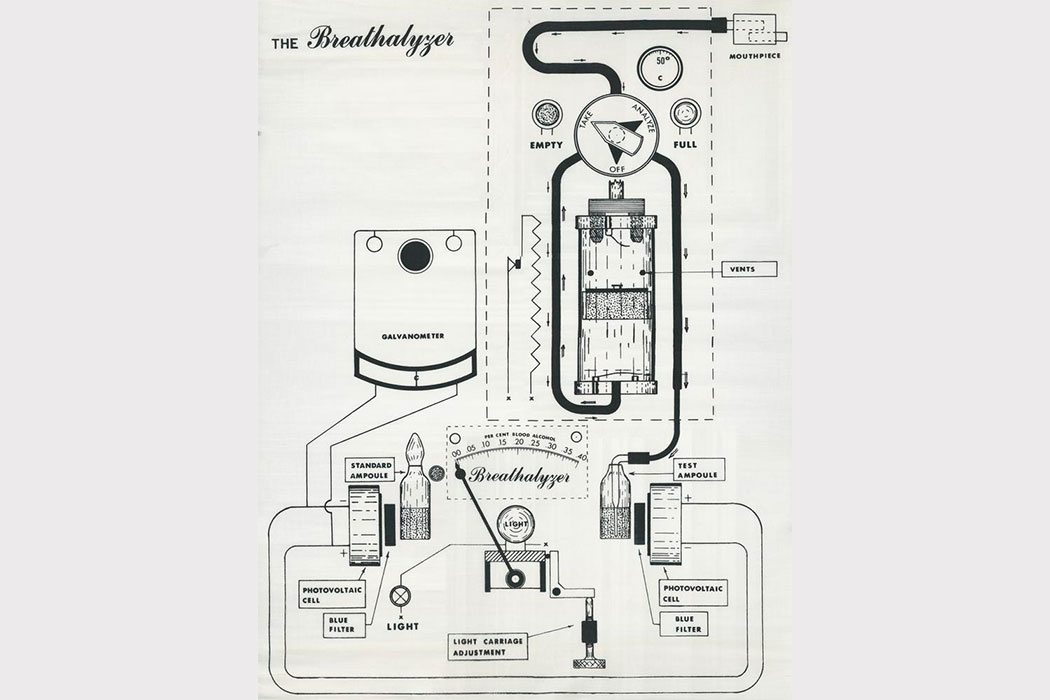

The device utilized a dilute solution of potassium permanganate in sulfuric acid, which would change color when exposed to a certain amount of alcohol, and while a complicated process, its operation could be taught to a qualified police technician.

Soon after Harger’s transference of the Drunk-O-Meter patent to the Indiana University Foundation, he teamed up with the Indiana State Police to put his device to practical use. There he met Robert F. Borkenstein, a Fort Wayne native with a background in color photography, who had joined the State Police Laboratory in 1936. In 1937, they together established a course to produce the first Drunk-O-Meter operators, comprised of 44 hours of lecture and laboratory work.

Thus, Indiana became the first state in the nation not only to train police cadets to use breath tests on suspected drunk drivers, but also to pass a law (in 1939) that defined “driving under the influence” purely in terms of blood alcohol content. The use of breath tests initially sparked a significant amount of controversy, with skeptics repeatedly challenging the reliability of the device based on halitosis, citrus fruits, and the simple fact that some people hold their liquor better than others. But police departments across the country, and the world, increasingly bought into the device, sending their cadets to Indianapolis to be trained under Harger and Borkenstein.

For all its usefulness, the Drunk-O-Meter was complicated, and its operation required strict supervision and constant retraining. In 1954, Borkenstein, working out of his basement and utilizing funds from the sale of his beloved English roadster, put together the first Breathalyzer, a device that was both more robust and simpler to use without sacrificing the reliability of its results. Shortly thereafter, in 1958, Borkenstein would join IU’s Bloomington campus as chairman of the Department of Police Administration, which later became the Criminal Justice Department. Borkenstein’s invention, and visible role in Bloomington, would further tie the university to research combatting drunk driving, not just in the state, but across the country.

Borkenstein’s landmark study in 1963, studying drunk driving’s effects on accidents in Grand Rapids, Mich., utilized interviewers from the Kinsey Institute under the rationale that if the interviewers could get honest answers about people’s sex lives, they could also get honest answers about drinking habits. Another example of the far-reaching effects of IU’s alcohol-testing acumen: for many years, IU’s role as the sole provider of Breathalyzer training for Alaskan State Police was written directly into the law.

IU’s modest investment in Dr. Harger’s strangely named device in 1936 helped provide the impetus for a worldwide change in law-enforcement standards, culminating in the Breathalyzer’s establishment as the most popular breath-testing device during the middle of the 20th century. It also established IU as a premier institution for matters of law enforcement and forensic science, for 20 years lead by Robert Borkenstein.

This article originally appeared in the August 2018 issue of 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine, a special six-issue magazine that highlights Bicentennial activities and shares untold stories from the dynamic history of Indiana University. Visit 200.iu.edu for more Bicentennial information.

Tags from the story

Written By

Sean Mentzer

Sean Mentzer, BA’18, is an intern with IU’s Office of the Bicentennial, and a contributor to 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine.