The Student Fee Hike of 1969

Those of us who attended Indiana University fifty years ago started 1969 with a sense of change and uncertainty. As I look back on 1969, I’m struck by how that year helped shape and sharpen my life and my careers as a lawyer, mayor, head of a national advocacy group, and professor in the years that followed.

After the state cut funding to IU in March 1969, the Trustees responded by raising tuition for the coming school year by 68 percent. At the time, this was not only a pocket-book issue for students, but male students who priced out of college could quickly be categorized as I-A by their draft boards and sent to war in Vietnam.

On April 17, 1969, I was elected IU student body president after speaking at a standing-room only meeting of the student senate. This representative body approved my call for a freeze of the tuition hike and a meeting between students and administrators. We named a seven-member student budget review committee, which met with the IU financial team for five hours on April 27.

On Monday, April 28, I moderated a meeting at the New Field House, with more than 8,000 students, to consider how to respond to the tuition hike. The next day we met with the faculty council to discuss our four “demands”—rescind the fee increase, give students a say over the budget, establish a graduated fee scale by 1970, and abolish tuition by 1972.

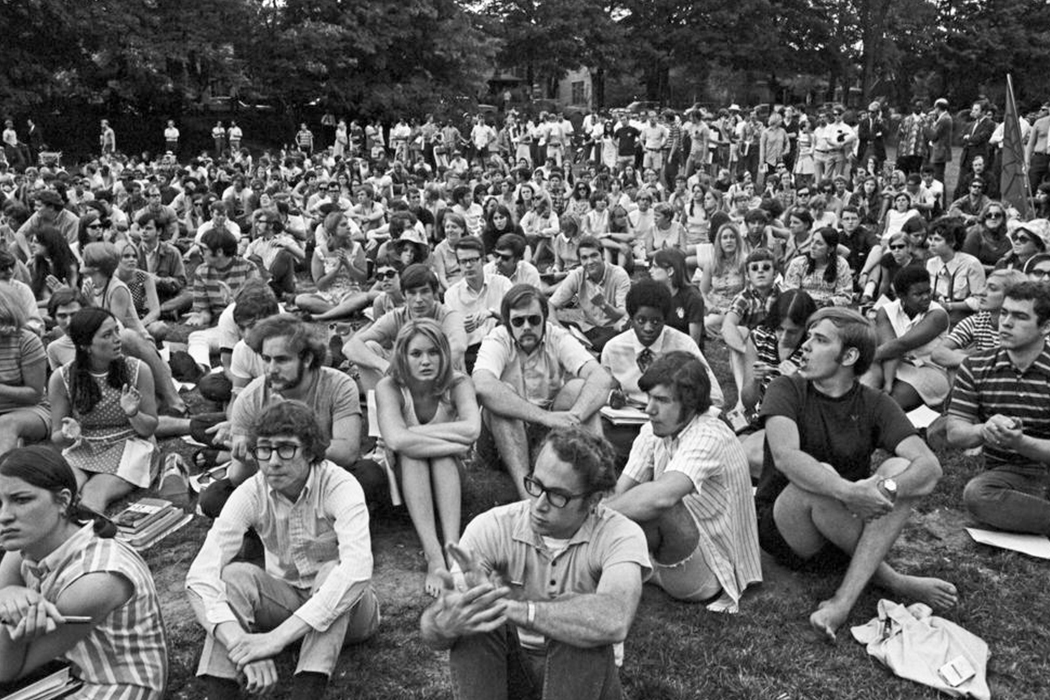

The IU administration responded negatively to these demands. Thus, at a meeting in front of Owen Hall on April 30, more than 3,000 students voted to boycott classes for the next two days.

The class boycott was supported by most IU students and a good number of the faculty. Many of us left campus to let folks back home know that the student concerns were legitimate, that this was not the work of “outside agitators,” and that the protests were responsible. Other students participated in teach-ins in their residence halls and Dunn Meadow, while others conducted letter-writing campaigns.

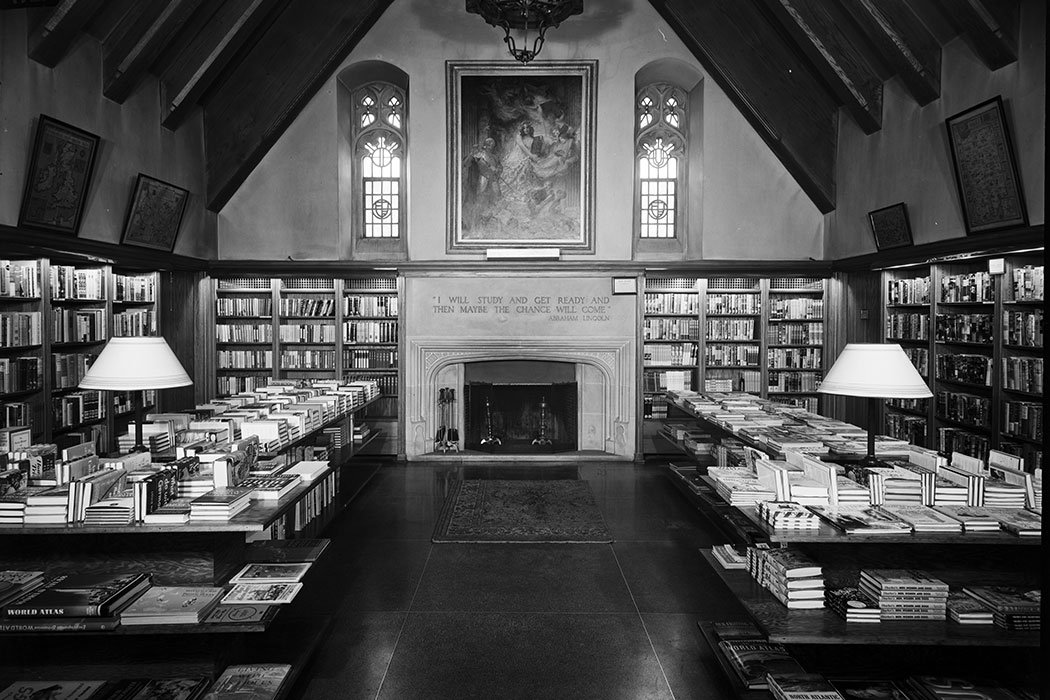

Heading into a rally in Dunn Meadow on May 1, 1969, we began to gain national attention as the “longest non-violent student protest” in the country. Later, a fire at the Student Library (now Franklin Hall), the work of a disgruntled employee, called this into question, but we continued to expand our efforts.

After another rally at Dunn Meadow on Sunday, May 4, and a vote to continue the boycott, the faculty council met for two days—interrupted by a bomb scare—to consider and eventually support our concerns.

On May 7, more than 5,000 students from Indiana’s public universities marched on the Indiana State House. Some of us tried to meet with Governor Edgar Whitcomb that morning, but he was nowhere to be found. I later learned from Richard Lugar, LLD’91, who was at that time the mayor of Indianapolis, that Whitcomb had warned him of violence from student protestors. But our march was peaceful, and part of my speech to the crowd, paraphrasing President John F. Kennedy–”those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable”—was broadcast on national television.

That same day, about 500 students walked out of the IU Founders Day ceremony. Former IU President Herman B Wells, BA’24, MA’27, LLD’62, praised the students for their peaceful exit, and sympathized with the concern “that universities not become a haven for the privileged classes.”

Things got even more hectic. The evening of the march in Indianapolis, I expressed concerns to the student senate about threats of violence—I’d been told that guns were being sent into the community—and the need to consider possible compromises. We were becoming increasingly worn out and shaken as the collective emotional temperature rose.

On May 8, we met with IU leadership during the day at Bryan Hall and then in the evening at Ballantine Hall in an effort to resolve the fee dispute. After back and forth discussions and a statement from the acting IU Chancellor John W. Snyder that our demand to rescind the fee increase would never be met, we reached a stalemate.

At 11:24 p.m., Rollo Turner, a graduate student whose “Black Market” store on Kirkwood Avenue had been fire-bombed by KKK members in December 1968, said “we’re going to wait here until the Trustees come.” Turner and others saw to it that the doors were chained shut, the window blinds pulled down, and no one was allowed to leave—with the exception of IU Administrator Joseph Franklin, who was in ill health.

It was tense. But things inside the room began to settle down as we discussed the budget and scholarships, and what it would take to get the Trustees to meet with students. Outside, law enforcement personnel—campus and local police in full riot gear, along with two platoons of state police who had been ordered to Bloomington by the governor—were gathering, court orders were being prepared, and plans were being made to enter the room with force if necessary.

Two hundred national guardsman were put on alert. Finally, Snyder was able to negotiate an agreement to end the “lock-in” in exchange for a promise that IU Trustees would meet with students within the next week. At 2:30 a.m., the lock-in ended.

On May 9, about 800 students met in Dunn Meadow and voted to end the class boycott. Little 500 took place with heavy security on May 10. Four trustees met with our student negotiating team on May 11, but little was accomplished beyond promises to look for budget cuts and try to increase financial aid. The fee protests were over.

In July, the Trustees did finally adopt a resolution guaranteeing more financial aid, urging a student voice be present in setting academic priorities, and establishing a financial aid review office. In my “State of the Campus” address on Jan. 8, 1970, I reviewed the lessons from that season of protest, which I described as “our grandest—and in a sense most tragic—moment of activism.”

While our goals and demands did not become policy, our issues had been taken to the people of the state, to Indiana legislators, to the trustees, administrators, and faculty with a conviction never before equaled by Indiana students.

Unlike so many other demonstrations from the 1960s, the fee protest was not just a one-day event. It still exhausts me to realize that we had nearly two and a half weeks of daily rallies and protest-related meetings, many with thousands of students of all political persuasions in attendance. For the most part, we avoided the destruction and violence that hit so many other campuses around the country. Those Spring 1969 protests would help make the anti-war protests of Fall 1969 even more effective, and ensure more student activism and progress on other issues of concern in the years to come.

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine, a special six-issue magazine that highlights Bicentennial activities and shares untold stories from the dynamic history of Indiana University. Visit 200.iu.edu for more Bicentennial information.

Tags from the story

Written By

Paul Helmke

Paul Helmke, BA’70, is the director of the Civic Leaders Center within the IU School of Public and Environmental Affairs, and a contributor to 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine.