A Big Bang: The IU Chemistry Demonstration Gone Awry

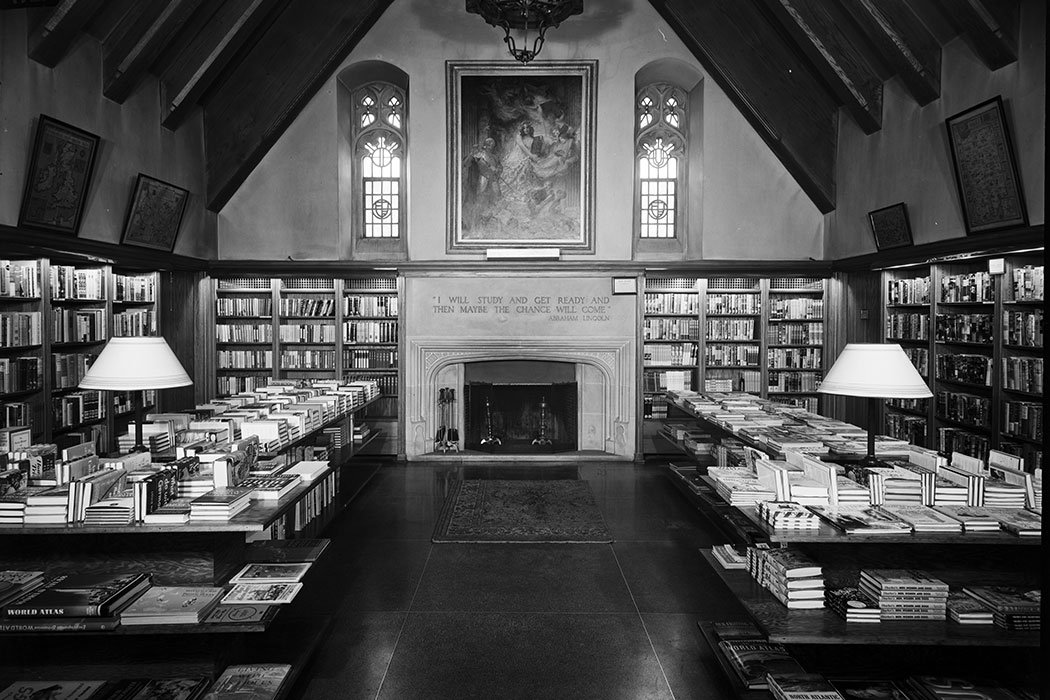

On the evening of April 24, 1957, in the auditorium of the chemistry building, Assistant Professor Charles Rohrer prepared the final demonstration for the Southern Indiana section of the American Chemical Society and local high school students. Rohrer poured liquid oxygen into a metal vat of sand and other compounds, then lit a candle at the end of a 10-foot pole. It was a demonstration that had been performed numerous times, both at IU and across the country. A big flame was supposed to shoot up to the ceiling and then dissipate back into the sand. Robert Appelman, BA’66, MS’67, PhD’93 recalls Professor Rohrer wanting to end the evening with “a big bang.”

No one was prepared for the bang that followed.

“You know, he’s farther away from this thing than we are,” Appelman recalls saying to his friend Peter.

Robert Appelman and Peter Vitaliano, both twelve-years-old at the time, were fond of exploring the science buildings at IU. They were convinced that they would one day become scientists, and when they saw that the chemistry department was holding demonstrations, they knew they had to go.

“We sat in the front row, but when we saw the final demonstration we were apprehensive,” Appelman said.

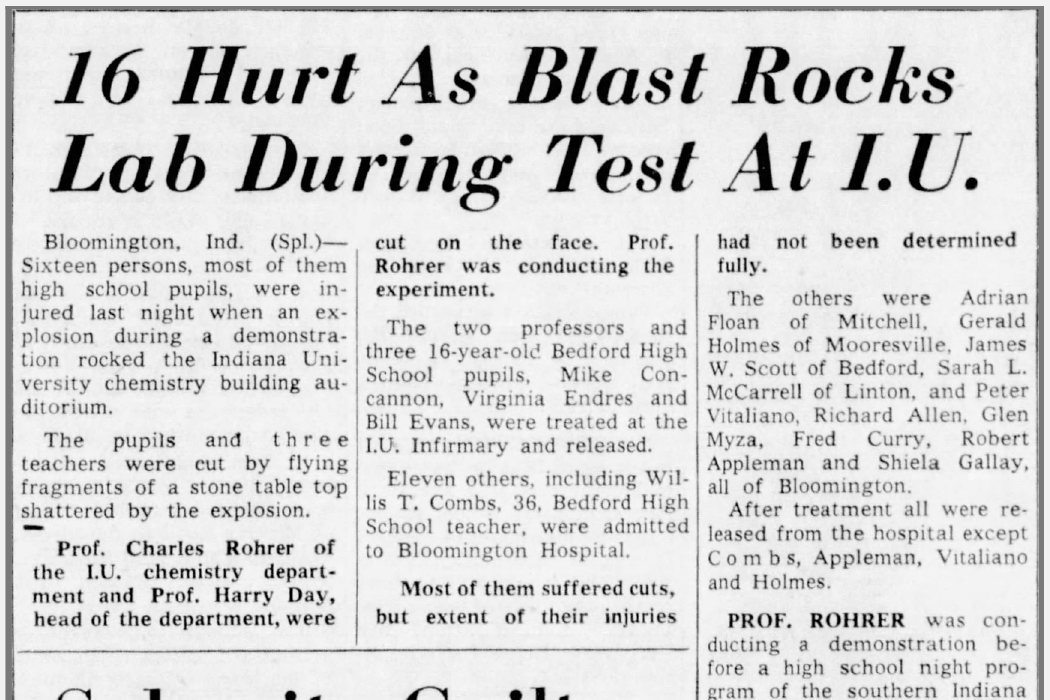

When the candle’s flame hit the liquid oxygen and sand mixture, something went wrong. Impurities in the liquid oxygen caused the apparatus to detonate. The explosion rocked the room, and according to Appelman, the blast, they calculated later, was equal to that of an anti-tank mine. Shrapnel from the soapstone table and metal cauldron went flying through the auditorium and a hole was ripped in the wall behind the blackboard. Appelman could not hear a thing at first because the force of the explosion pushed him back into his seat.

“It was even worse than a belly flop from a high dive into water,” Appelman said.

He remembers seeing smoke, haze, and debris littered around the room. Slowly, his hearing came back and he heard some whimpering, some crying that quickly got louder. He looked down and saw blood on his pants. He got up and walked into the hall, in a daze until he noticed he was leaving a trail of blood drops behind him.

“My arm was dangling; I had no control over my arm,” Appelman said.

Chemistry faculty and students leapt into action and attended to the injured spectators. One student put Appelman’s right arm in a tourniquet to stop the bleeding. Pieces of soapstone had shattered the ulna in one arm and cut up his other arm, and a piece of metal had burned his chest. When doctors at Bloomington Hospital evaluated him they were concerned that they’d have to amputate his arm.

“Dr. Philip Todd Holland was my savior,” Appelman said.

Dr. Holland, one of the top orthopedic surgeons at the time, referred Appelman to a colleague in Indianapolis, who performed a bone graft—saving his arm.

Appelman spent three months at Riley Hospital and wore a cast for six months. He jokes that it made him mostly ambidextrous because he could not use his right arm for anything. Unfortunately, Appleman’s injuries have had lasting consequences–he couldn’t play sports or join the military, and he still has significant mobility limitations.

“It’s just been this constant reminder that’s been following me my whole life,” he said.

In an attempt to make amends, IU paid for all of Appelman’s medical costs and provided him with a scholarship that covered the full cost of his undergraduate education.

Appelman doesn’t fault Professor Rhorer for the explosion. But sadly, Rhorer felt so guilty about the explosion that he had a nervous breakdown and left the university in 1958.

While Appelman is in great spirits today, he recalls the frustration he felt over the years when people didn’t believe his story. There is hardly any record of the explosion, aside from a small handful of local newspaper articles, none of which have been digitized, and some brief notes in the archived minutes of the May 18–21, 1957 Board of Trustees meeting under the title “Catastrophes This Year.”

However, in June 2018, Appelman recorded the events of the chemistry explosion for IU Bicentennial’s Oral History Project. His full story is now preserved in the official institutional history.

“I really appreciate this opportunity to tell you about it,” he said. “This should provide a trace.”

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine, a special six-issue magazine that highlights Bicentennial activities and shares untold stories from the dynamic history of Indiana University. Visit 200.iu.edu for more Bicentennial information.

Tags from the story

Written By

Zachary Vaughn

Zachary Vaughn, PhD’19, is a graduate assistant with IU’s Office of the Bicentennial, and a contributor to 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine.