A Day in the Life of a 19th-Century IU Student

Descending from the chugging train, the freshman clutches his trunk. The air is full of ashy fumes. The young man surveys the bustling train station: newcomers like him take in first glances of their new home, while others wave farewell to those departing.

Outside the station, there is the clip-clop of horses pulling buggies and stagecoaches. The freshman walks a couple miles before reaching the house of Dr. Murphy, who greets him and accepts his $5.00 monthly payment to rent a room. The small room is scantily furnished, but the freshman makes do.

That night, he pulls out a leather-bound book. By candlelight, he writes “Journal” at the top of a page and begins to recount his day: “1857. Friday, September the 25th. First impression of Bloomington not very good.”

For students at Indiana University during the school’s adolescent years (1850–1870), move-in day was quite different than it is today. Until 1853, most people journeyed to Bloomington by horse-drawn stagecoach on roads that were pockmarked with tree stumps, which made travel rickety if not outright nauseating.

Fortunately, 1853 brought railroad connections to Bloomington, with express trains that could go a hair-raising 15 miles per hour. All trains stopped in Bloomington at the Monon Railroad Train Station, where today’s B-line Trail intersects Kirkwood Avenue and Fourth Street.

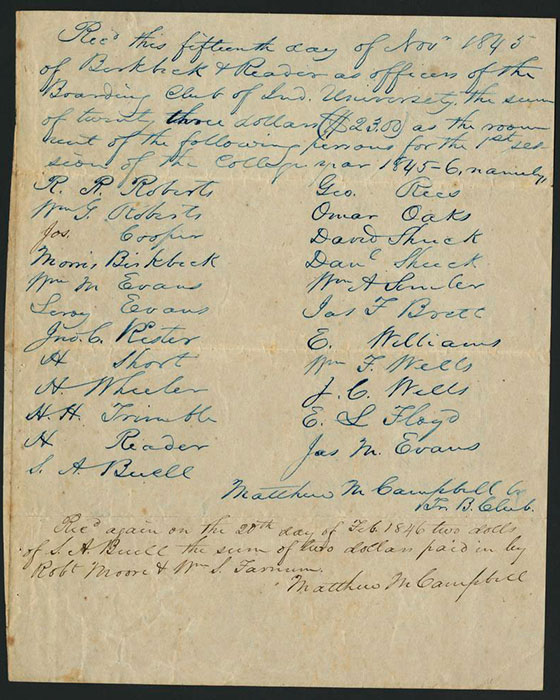

Once in Bloomington, students had two options for room and board. They could either live in boarding houses, which were similar to dormitories, or live with local families.

One boarding house was owned by Indiana University and was located on the southwest corner of the Seminary Square campus. The simple two-story building included barely furnished rooms on the second floor, strict rules, and a professor as the literal next-door neighbor.

After a couple days of settling into his new room and gaining a roommate, the freshman goes to enroll. He treks to campus—a few sloped acres with four scattered academic buildings. Entering the proper room, the freshman meets with university faculty, who assign him his three courses for the semester.

The first course is algebra. In the classroom, he sits erect, shoulder-to-shoulder on a bench with two other freshmen. As lecture begins, the professor calls upon the freshman. With a deep breath, he stands and recites from memory a lesson he had studied the night before. After an hour of algebra, students bee-line to their next class, and the routine of lecture and recitation proceeds for English literature, and then again for physical geography.

On Saturday morning, the freshman goes to the campus chapel to hear a sermon from the university president, Reverend William Daily, before attending composition with Professor Kirkwood.

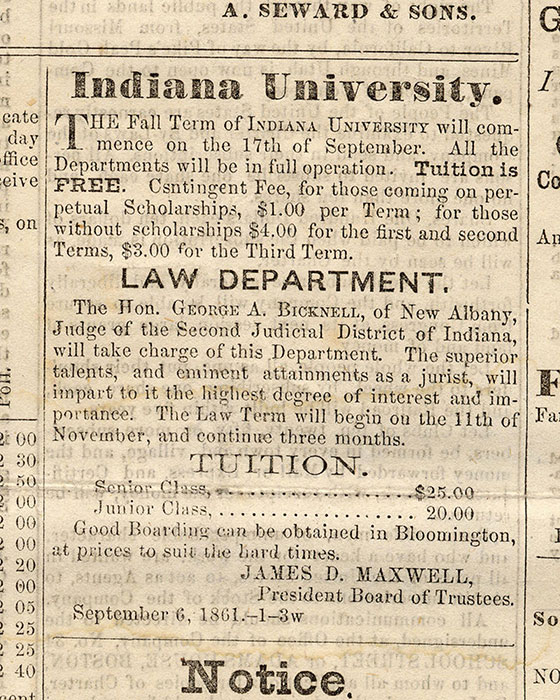

Academics from 1850 to 1870 were limited compared to today’s diverse array of disciplines and classes. Higher education during the majority of the 19th century was ruled by the classical education model; students took prescribed curricula each year that focused on classical languages, math, and philosophy. Students could not choose majors or electives, and classes were called recitations because students were required to orally recite lessons by memory in front of the class.

Beginning in the 1850s, Indiana University added science courses, and the first bachelor of science degree was awarded in 1855. Thirteen years later, students in the sciences track were given the option of taking either classical or modern languages—the first move toward academic freedom of choice.

The freshman’s homesickness finally begins to fade halfway through the semester when he joins the Philomathean Society. At the first meeting, the society president calls the house to order and a chapter in the Bible is read. After these formalities, the freshman is ushered into the room and initiated. He sits with his new society comrades, who debate the topic “Should the government build the Pacific Rail Road?” Arguments are heard, speeches are performed, and the meeting concludes at 11:30 p.m., at which time the freshman walks back to his boarding house.

When not reciting from textbooks and studying, what did mid-19th-century students do? More writing and oratory, of course!

Literary societies dominated social life before fraternities and sororities became popular near the turn of the century. The two most prominent societies were the all-male Athenian Society and Philomathean Society. The Hesperian Society, the first women’s society at IU, was started in 1870, three years after Sarah Parke Morrison enrolled as the first female IU student.

The Athenian and Philomathean Societies had their own halls, where members attended weekly meetings that sometimes lasted until midnight or later. These meetings usually consisted of debates on hot topics of the time, original speeches and poetry, and sometimes music.

In addition to these pursuits, some students passed their time by exploring the surrounding forests and caves, hunting, watching horseracing in nearby Bedford, and playing pranks on fellow students and professors.

Then there was courtship. Even before the first female students, women who attended the Monroe County Seminary and Female Institute were allowed to sit in on some lectures beginning in the 1850s. The female presence on campus created the precedent for campustry. Campustry was a romantic ritual on campus in which couples would spend sunny days chatting, flirting, and reading to each other under the shade of trees.

“Then Commencement Day. All went early to get good seats and hear the boys speak – of Greece and Rome – every one of whom their friends expected would be President or Senator (and) of course never any thing less than a representative in Congress. Every graduate in that day had to make a speech, if he did not it was generally believed he would never amount to anything.”

—John D. Alexander, Class of 1861

Vignettes based on the diary of John C. Wilson, who was a freshman at IU from the fall of 1857 to spring of 1858, “Recollections of Indiana University” by John D. Alexander, class of 1861, and History of Indiana University by James Woodburn, class of 1876.

This article originally appeared in the January 2018 issue of 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine, a special six-issue magazine that highlights Bicentennial activities and shares untold stories from the dynamic history of Indiana University. Visit 200.iu.edu for more Bicentennial information.

Tags from the story

Written By

Kayla McCarthy

Kayla McCarthy is currently a senior at IU, and is a contributor to 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine.