The Man Who Brought Art to IU

In the summer of 1896, a twenty-six-year-old art historian and recent graduate of Harvard University, Alfred Mansfield Brooks, made the long trek cross country to the relatively young Indiana University [campus] in the remote town of Bloomington. He brought with him the ideology of his teachers Charles Herbert Moore, Charles Eliot Norton, and Harold Broadfield Warren, who were disciples of the English artist and theorist John Ruskin.

Brooks thought of IU as a direct descendent of the grand traditions founded at Oxford and Harvard Universities, writing in 1900: “In size and equipment they differ; in purpose they are one.”

He became the first art instructor in the new Department of Freehand and Mechanical Drawing, which did not offer a degree. The curriculum focused on an appreciation of the works of the great masters, rather than on practical art training. Nonetheless, the administration understood this to be serious work on par with other academic subjects, not “an opportunity for school girls to learn a smattering of painting.” Brooks was paid an annual salary of $800 and given an equipment budget of $250 with which to outfit a single lecture and drawing room on the third floor of Kirkwood Hall.

He taught courses on drawing, architecture, the principles of delineation, color, chiaroscuro, and the history of painting. The program, which grew into what is now the School of Art, Architecture. and Design and the art history department in the College of Arts and Sciences, is believed to be the third oldest art department at an American university or college.

Brooks’s youthful enthusiasm and East Coast sophistication made him a bit of a novelty on campus as well as the butt of jokes in the Arbutus yearbooks. An 1897 cartoon shows him with a topcoat and cane, perhaps in Dunn’s Woods, with the caption, “are there bears in those woods?”—hinting that he is a city fellow who is unfamiliar with rural life. The “bears” appear to be small animals, an odd baby, and a girl with a butterfly net. The accompanying verse, “students of art,” jokingly suggests the dubious impact of Brooks’ classes on the aesthetic choices of his students, whose newfound love of art had led to a rash of dorm rooms decorated with food product labels.

A caricature from 1908 shows him dressed as a fireman, referring to a time when he apparently discovered flames in Wylie Hall. As with the other captions, the humor focuses on Brooks as an aesthete outsider (describing him as member of the “Order of Bachelors” and an expert on etiquette), stating that he had yelled “Conflagration! Conflagration!!”—a word unfamiliar to the local firefighters—and that when dousing a henhouse fire he did not even get his “trousahs” uncreased.

The biographer of Frank Aydelotte, former IU undergraduate and friend of Brooks, described the fine arts professor as a character with an odd appearance and unusual personality, but who was remembered for his wit and “puckish glee,” fine draftsmanship, worldly knowledge of art and literature, and brilliant, racy monologues.

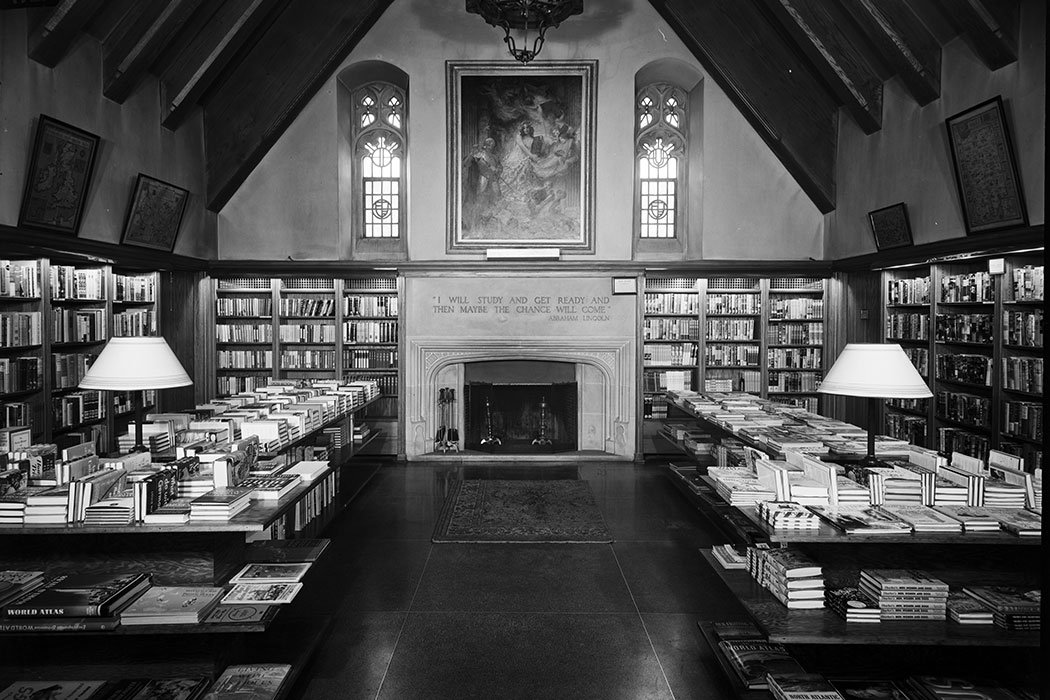

Brooks professed a nineteenth-century belief in the power of art to transform people’s lives and felt that a “treasure-house of architecture, sculpture, and painting” was as essential to the study of the liberal arts at a university’s libraries. Although IU President Joseph Swain, BA 1883, MS 1885, worried about Brooks’ youth and inexperience, he felt that “on the whole he has the right training and spirit and I would rather risk him than a man who has less culture and outlook.”

Brooks was promoted through the faculty ranks from instructor to professor. In 1911, IU awarded him an honorary master of arts and that same year he took on a dual role as the first print curator of the John Herron Art Institute (now the Herron School of Art and Design).

In addition to books and photographs, Brooks acquired a collection of plaster casts of classical sculptures and original artworks to use as teaching aids and display in small traveling exhibitions. The works on paper were hung on the classroom walls or passed around for instruction and copying, a traditional means of art education. Brooks counted his early “museum” among his proudest accomplishments at IU, stating: “I take satisfaction in the knowledge that [the department] is equipped with not a few drawings which will always ensure its distinction, and give real inspiration to its best students.”

By the mid-1930s, the fine arts collection boasted more than 1,000 items—primarily prints and drawings. Prior to the Eskenazi Museum of Art’s founding in 1941, the early fine arts collection offered valuable insight into the teaching methodology and artistic tastes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Recognizing the importance of the study of art in the original, Brooks felt that direct encounters with actual prints would awaken greater appreciation and critical thinking in his students than could be achieved merely by seeing reproductions after the masters. As such, old master prints (in the absence of expensive paintings) were sought for the fine arts collection. Although small in number, these works formed the core of the teaching curriculum. Among the earliest treasures were works by Albrecht Dürer, J. M. W. Turner, and William Hogarth.

Prints and drawings by British artists, who produced “architectural picturesque” views of medieval castles and cathedrals, were particularly favored, since they offered an interdisciplinary approach to students interested in art, architecture, history, and literature.

In 1912, Brooks took the quality of the teaching collection to the next level by buying fourteen drawings by the American artist John La Farge. Then, in 1916, he requested $250 from the IU Board of Trustees to purchase some eighteenth-century drawings and prints from the estate of William Ward, a renowned student and copyist of John Ruskin.

Brooks published an article highlighting IU’s English drawings and watercolors in Art in America (April 1918). In doing so, he set a precedent for using fine art to elevate the status of the university and sowed the seeds for a museum-quality art collection as being essential to its mission. Brooks left IU in 1922 to head the new fine arts program at Swarthmore College. The early fine arts collection remained largely unknown until the 1990s, when I rediscovered a 1936 appraisal in the papers of Professor Diether Thimme.

Highlights appeared in the museum’s 1996 exhibition, Art in the Original: Selections from the Early Fine Arts Collection. While the plaster casts are now lost, many of the works on paper will be accessible for classes and public viewing when the Eskenazi Museum of Art reopens in late 2019, in plenty of time for the university’s Bicentennial and the 125th anniversary of the first art classes taught at IU.

This article originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine, a special six-issue magazine that highlights Bicentennial activities and shares untold stories from the dynamic history of Indiana University. Visit 200.iu.edu for more Bicentennial information.

Tags from the story

Written By

Nanette Esseck Brewer

Nanette Brewer, BA’83, MA’04, is Lucienne M. Glaubinger Curator of Works on Paper at the Eskenazi Museum of Art, and a contributor to 200: The IU Bicentennial Magazine.