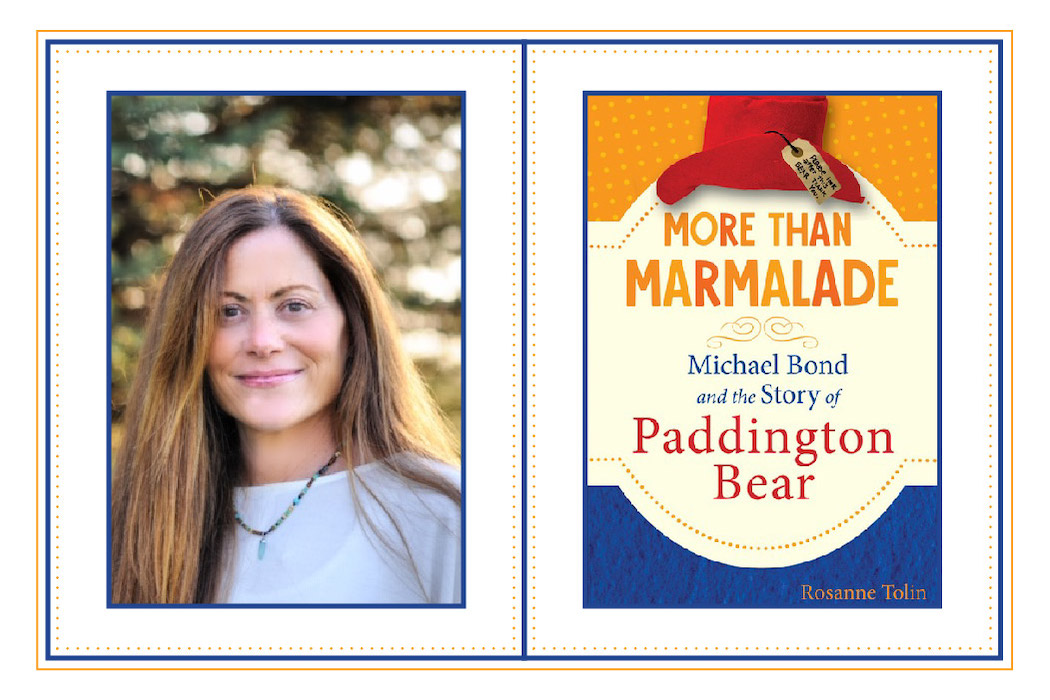

Excerpt: More Than Marmalade: Michael Bond and the Story of Paddington Bear

Michael Bond never intended to be a children’s writer. Though an avid reader, he was by no means a model student and quit school at 14. He repaired rooftop radio transmitters during the bombing of Britain in World War II and later joined the army. He wrote about the war and more, selling stories here and there.

One day, while searching for inspiration at his typewriter, hoping for a big story that would allow him to write full time, a stuffed bear on top of the shelf—a Christmas present for his wife—suddenly caught his eye. Bond poured his personal feelings about the events of his era—the refugee children his family had hosted in the countryside, a war-torn country in recovery, the bustling immigrant neighborhood where he lived—into the story of a little bear from Peru who tries very, very hard to do things right. The result was A Bear Called Paddington.

An incredible true tale, More than Marmalade: Michael Bond and the Story of Paddington Bear is the first biography about the writer behind the beloved series. Author Rosanne Tolin reveals how world history, Bond’s life, and 1950s immigrant culture were embedded into Paddington’s creation, bringing middle-grade readers a delightful, informative, and engaging book with a timely message of acceptance.

Chapter Seven

All About Paddington

As Michael pressed the keys of his typewriter, he paused often to look at Paddington. So many questions spun in his head. Where did bears live? Why would a bear travel to London? Would the bear want to visit museums or would he want to find a new home?

Michael talked to Paddington Bear who sat perched on the fireplace. While he wrote the first Paddington story, he asked questions of his stuffed companion. And for every question Michael asked, his imagination provided the answer.

“What kind of bear are you?” Michael wondered. After pondering it for a moment, he guessed Paddington was an African bear.

“A bear from the wild bushlands of Africa!” He hammered out a few more sentences on his typewriter.

Then he looked up at Paddington. “But how did you get to Paddington Station?”

The stuffed bear looked a little forlorn.

“You might wonder whether I really want to hear your sad story,” Michael said. “I do want to hear it.”

He shifted around to face Paddington. He was about to say something important, and he wanted the bear to understand every word.

“The world is filled with grief,” Michael said. “I have seen quite a bit of it in my life. Whatever sorrow you have felt, please share it with me. Sharing it might make you feel a bit better.”

Paddington still seemed a bit gloomy. But he also looked a little hopeful, as if he might have found a friend who would understand.

“Ah, I see,” Michael said. “Before you came to England, both your parents died.”

He shook his head. “Heavens! How awful for you. How did they die?”

Was that a tear in Paddington’s eye, or sunlight reflecting on its smooth glass surface?

“An earthquake, you say?” Michael asked. “Dreadful. They were both gone just like that.”

Michael snapped his fingers. The ideas spilled from his head to his busy hands.

“How did you manage after your parents died?” he asked Paddington as he tapped on the keys. They creaked with wear. “Were you old enough to take care of yourself?”

Michael was lost in thought for a moment. Then he knew that Paddington’s aunt must have taken him in.

“Just like my aunties!” Michael said. “They were ever so kind. I understand what a comfort your Aunt Lucy must have been.”

He quickly wrote another page of the story.

“Say,” Michael asked, “how did you get from Africa to London? Bears can’t swim that far, can they?”

He chuckled at his own foolishness. “Certainly not! You must have come over on a boat, like many other immigrants.”

He stared at Paddington. The toy was small and cuddly, but a real bear would be much larger. It would frighten the passengers. The harbormaster would never have sold a ticket to a bear. Paddington must have found a different way to board the ship.

“You snuck onto the ship when no one was looking,” Michael mused. “You were a stowaway! You tucked yourself into a lifeboat where no one would find you.”

He pounded nonstop at the typewriter for the next ten minutes. Finally, Michael stopped for a moment. “But what did you eat? That was too long a journey to go without food.”

Michael’s brows creased. He thought about what a bear might eat during a sea voyage. Would he lean over the bow and scoop fish out of the water? No, someone would see him and scream in fright. Would he catch bugs and nibble on them every night? No, bugs couldn’t fly far out over the ocean.

“A-ha!” he said. “You ate the food you had packed. What might fit in such a small suitcase? It must be something sweet, that bears like to eat. Perhaps a jar of orange marmalade!” Marmalade was jelly made from orange juice and peels. Michael knew he’d discovered Paddington’s favorite, sticky meal.

The more Michael talked to Paddington, the more he learned he was a very brave bear. Like many children of the war, courage was necessary for survival. Michael recalled that Harvey, his literary agent, was once told his name was written on a foreboding list. He would be captured by the Nazis and shipped off to a concentration camp, a place where he would likely be killed. At the time, Harvey was about to become the youngest judge ever in Germany. But he swiftly fled to England instead, with just a suitcase and 25 pounds to his name.

That amount would be worth around $625 today—not enough for more than a few weeks of food and shelter. With so little money, finding a new home was hard. Michael thought about how lonely Harvey must have been with no friends to help out.

He also remembered the children who had showed up in Reading. The boy he met who held the gas mask had been happy about not having to go to school. Many of the other children had been scared. They missed their parents and friends, and struggled to remain in contact with them. Their hopes for a happy reunion quickly dwindled as the days and weeks went by.

“So,” Michael murmured to Paddington. “You also would have been lonely when you showed up in London. And you certainly would have shivered. The climate here is much different than in Africa.”

To solve this problem, Michael gave his character a warm, blue coat. In fact, it was the same type of duffle coat Michael wore to work every day. To keep the bear’s head warm, he gave Paddington a bright red hat. It was just like the one Michael wore when he rode his motor scooter.

For ten days straight, Michael sat at that typewriter and tapped out one word after another. Whenever he got stuck, he asked the stuffed bear a few more questions. He learned that Paddington was polite, and that most times, his good manners helped him do things the right way.

Because he was a stranger to the city of London, Paddington made a lot of mistakes, but every misstep taught him something new. Mr. Gruber, the Hungarian antique shop owner Paddington befriended, also gave helpful advice. The two enjoyed their “elevenses” together—a midday snack, often consisting of hot cocoa and chocolate buns, where Mr. Gruber offered his wisdom as an older refugee. Not everyone Paddington encountered cared about kindness, however. Those people always received a hard stare that made them blush from embarrassment for their rude behavior.

“Who taught you that neat little trick?” Michael wondered. “I know! Your Aunt Lucy taught you that.”

Finally, after all that waiting and wondering and tapping away at the typewriter keys, the story was finished. Michael packaged it up and mailed it off to his agent.

“It was the first time I had written for children,” Michael once said. “But I didn’t have the age of my readers in mind. I was writing it for myself.”

As the story of Paddington Bear unfolded in many more books, Michael would discover more about this loveable little bear. Along the way, Paddington would also become Michael’s moral compass. But before any of that could happen, the first book he bashed out in only one week and a half had to be bought by a publisher. How many rejection slips would Michael receive this time?

For over a month, Michael waited to hear from his agent. Every time he got home, he asked Brenda if the phone had rung. She was pregnant, and Michael worried that she wouldn’t be able to reach it quickly enough.

“Stop your fretting,” she said. “I am never far from the phone. I always pick up before the caller hangs up.”

“So, then?” Michael asked. “Did Harvey call?”

“Not yet, love,” she said. “I’m sure he will call soon.”

Michael continued to worry. What would Harvey think of the story? Would he be upset that the story was for children? Would he know any publishers who were interested in children’s books?

The waiting was endless. Then, just as Michael and Brenda were sitting down for dinner one evening, the telephone rang. Michael jumped from his chair and snatched the receiver.

“Hello?” he said. “Hello? Can you hear me?”

“I can hear you just fine,” Harvey said.

Michael was bursting with anticipation to hear Harvey’s thoughts about the story. But being rude was out of the question. So, he first asked how Harvey was doing, and they chatted a bit about Brenda. Finally, at long last, Harvey cleared his throat.

“Well, then. About this story,” Harvey began.

“You mean A Bear Called Paddington,” Michael said.

“Yes, Paddington,” Harvey said. “There is a slight problem.”

Disaster! Michael glanced at the stuffed bear on the mantle. What could be wrong? Perhaps Harvey didn’t like bears. Maybe publishers would think that Michael was trying to copy Winnie-the-Pooh. A million earthquakes shook his thoughts.

“What might the problem be?” Michael asked.

“There are no bears in Africa,” Harvey said. “At least, not today. The Atlas bear used to live there, but the last one died in 1870.”

“I see.” Harvey was always full of facts that got right to the point.

Michael glanced at Brenda. She was watching him carefully. She could tell that something was wrong, but she couldn’t hear Harvey’s voice.

“Well, then,” Michael said. “Perhaps Paddington comes from a different country. A place that still has bears.”

“Changing that would be a wise choice,” Harvey said.

“Otherwise,” Michael said, “did you like the story?”

“Very much!” Harvey said. “I think we have a real chance at getting this published.”

“You don’t know how happy that makes me!” Michael said.

Brenda grabbed her round belly and gave it a pat. She didn’t know exactly why her husband was happy, but it had to do with his writing. The news must be good.

Harvey made a few more suggestions and told Michael to send him a fresh copy after he had made the changes. The moment Michael hung up, he celebrated with his wife. Right after dinner, he went back to the typewriter to work up a new version of A Bear Called Paddington.

This time around, Paddington became a Peruvian spectacled bear. The spectacled bear is closely related to the Florida spectacled bear, which lived in North America long ago. The spectacled bear is the only species of bear native to South America. Although it is a carnivore, or meat eater, it eats very little meat. That fit right in with Michael’s story of a kindhearted bear that loved marmalade.

But the bear’s fur is most often black, with a tan face framed by black patches. That didn’t fit Michael’s character at all. He pictured Paddington as the same color as his stuffed bear. However, some spectacled bears are light brown, while others have a reddish tint. Paddington could be tan, just like Michael had imagined.

Everything seemed to be falling into place for Michael and Paddington Bear. Then Harvey sent the story to publishers. Time after time, the publishers read the story and said no. The rejection slips piled up again, seven in total. Michael could only worry, and anxiously await more responses.

He often skipped sleep to sit at his typewriter. A few minutes here, an hour there, were stolen from his days. After all, his grandfather had said to never give up! One day, Michael knew, he would make it as a writer. Finally, his agent called again.

“Michael,” Harvey said, “Collins wants to buy your book.”

“That’s great news!” Michael said, jumping up from his desk chair. “William Collins publishing house has been around for a while, hasn’t it?”

“Over a hundred years,” Harvey said. “And the deal is fair. Are you ready to hear this?”

Michael held his breath. He managed to say, “Yes.”

“Collins is offering 75 pounds for the story,” Harvey said.

That would be worth nearly $2,300 today.

“Sold!” Michael said.

After the contract was signed, things moved quickly. Peggy Fortnum, an illustrator, was hired to draw the pictures. The book was published in 1958—the same year Brenda gave birth to their first child, a daughter they named Karen. That brought a lot of joy to their crowded apartment. Between helping Brenda with the baby and working, Michael was busier than ever.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, check out our interview with Rosanne Tolin, or purchase her book.

Excerpt from chapter seven of More Than Marmalade: Michael Bond and the Story of Paddington Bear by Rosanne Tolin. Copyright © 2020 by Rosanne Tolin. Reprinted by permission of Chicago Review Press. All rights reserved.

Tags from the story

Written By

IUAA Staff